Understanding Year End Practice & Dön Season

by Russell Rodgers

In the Tibetan Buddhist tradition, there is a period before the Tibetan New Year in the late winter/early spring when accumulated karma comes to fruition and societal obstacles arise. This year, between January 30 – February 8, we will do “Mamo Practice” to purify obstacles of the old year. Then, on Shambhala Day, February 10, we can start afresh with the new year.

At this time, when we look around the world, there seems to be no relief from suffering and no escape from the karmic baggage we humans have created. On a personal level, accidents, sickness and general bad luck tend to be on our minds. From an ordinary, non-Buddhist point of view, we could say that we have survived the winter solstice but the harshness and darkness of winter are still dragging on. The fresh promise of spring and bliss of summer have not yet arisen.

This time of obstacles is known as the “dön season.” Döns are negative forces that arise out of the environment, causing humans to do things that are self-destructive and mindless. This could take the form of sudden fits of anger or madness, or making bad decisions that will lead to misfortune. Döns produce sudden, unexpected neurotic upheavals. Car problems, colds or flu could be considered döns. On a personal level, the best protection against döns is increasing one’s mindfulness. Therefore, this season is an especially good time for meditation practice.

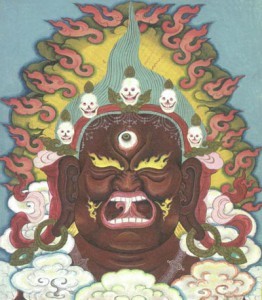

They are symbolized in the form of deities called dakinis. Mamos are mostly a worldly variety of dakini, unenlightened aspects of the feminine principle. (Mamos can be enlightened, however, like Ekajati.) In Tibetan Buddhism, insight or prajna, possessed by both men and women, is seen as an aspect of the feminine principle. Mamos become enraged when people lose touch with their own intelligence, and therefore with reality. Mamos cause large-scale problems: fighting and civil discord, famines, plagues, and environmental calamities. In the mamo chant, it says that they “incite cosmic warfare.”

Tibetans depict mamos as fierce and ugly demonesses, black in color, with emaciated breasts and matted hair. They appear with sacks full of diseases. They cause havoc with a roll of their magical dice, creating pestilence and warfare. They are associated with the karmic consequences of degraded personal or societal actions. Their enraged response might be in proportion to the karma accumulated, but it could also be unpredictable and completely out of proportion. Similarly, we know that there have been many cases where small provocations have produced great wars.

Many mamos were tamed, or at least partially tamed, by Padmasambhava, a great adept of the eighth century. Tibetans call him the “Second Buddha.” According to the legend, when he encountered mamos manifesting in the form of various natural and cultural obstacles on his way through Tibet, he overcame them and bound them by oath (samaya) to protect the dharma.

What does this mean now, in the West? In tantric Buddhism, obstacles arise when we lose insight, and those very obstacles, in the form of döns and mamos, remind us to increase our mindfulness and awareness.

If we are able to remember and invoke some of Padmasambhava’s pure vision with respect to obstacles, the wrathful activity of the mamos becomes tamed as part the path. It helps to know that mamos and döns are actually inseparable from our own minds—which is what makes the taming possible. Giving them names and personalities just enables us to tune into their energy.

In Tibetan monasteries, for several days preceding the New Year, monks do ceremonies, all day and through the night, invoking protectors and wrathful deities to clear obstacles. At the end of this period, the karmic baggage from the old year is symbolically concentrated into a giant sculpture, which the monks burn to the accompaniment of firecrackers, horns, cymbals, chanting, lama dancing and drums. After the practice ends, there is a “neutral” day where one cleans one’s house to expunge the unwanted traces of the old year. Then, on the first day of New Year, one does a new year’s day practice and on subsequent days people visit each other in their homes and there is general feasting and celebration. There is a strong sense of a fresh beginning.

The mamo practice begins by chanting the Seven Line Supplication to Padmasambhava. We ask him to please approach and grant his blessings. We do this to establish some sense of presence of Padmasambhava’s ability to see through what may look to us like “bad energy.” Following this, we do some protector chants accompanied by a drum. Protectors symbolize feedback from reality, the constant arising of coincidence that shapes our lives.

Next, vajrayana practitioners do a Vajrakilaya practice, just as Padmasambhava did before going to Tibet. Vajrakilaya is dark green and surrounded by flames of wrathful compassion. This is not “feel-good” compassion, but the fiery quality of uncompromising destruction of egoistic tendencies. These are tendencies that may seem familiar and comforting in the short run, but will inevitably produce alienation and suffering in the future. Vajrayana practitioners do this practice in order to identify with wrathful compassion.

Shamatha students can tune into wrathful compassion by seeing thoughts as thoughts in a direct and uncompromising way. The compassionate aspect is that we acknowledge their underlying energy and their right to be there, even as we allow the story line to dissolve into space.

But why would we do such a practice? In our culture we may occasionally feel “hounded” by misfortune, but we do not, except perhaps jokingly, attribute it to agents like mamos, gremlins, or döns. These concepts are foreign. Let’s digress for a few paragraphs to talk about what we are being hounded by, and why we might do this practice in the first place.

Ekajati: Queen of the Mamos, thangka painting by Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche

Ekajati: Queen of the Mamos, thangka painting by Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche

As always, with protectors, döns, mamos, and other deities, one can see them as external to oneself, or as aspects of one’s own mind. If you contemplate for a few minutes, you will realize that both the sense of self and the sense of an external “other” are interpretations in the mind. As you read these words, the paper or the computer screen probably seems to exist outside you, but they are actually images in your mind. You may think that these images are faithfully assembled from electric impulses traveling down your optic nerves, but the idea of electric impulses and nerves is, again, a thought in your mind. So, not only do the labels and interpretations of phenomena reside in our minds, but the actual experience seeing an appearance does as well. So appearance and mind are the same. Obviously this has implications for the sense of being “hounded.” It also means that by doing rituals that are directed outward, towards mamos and döns, we are also working on our own minds. As we pacify one, we pacify the other.

In rituals like this, we practice awareness of the words as we say them, knowing that the words are just words. This is similar to the experience of thoughts vanishing into emptiness when we see them in meditation. At the same time, we allow the words to create a path of meaning that we can explore. At the end, we rest in the wordless dimension of this meaning. This is now our point of contact with reality.

After the protector chants and the Vajrakilaya practice, we get into the heart of the mamo practice with the main chant of this practice, entitled “Pacifying the Turmoil of the Mamos.” Here, we remember that the mamos become active when people, especially practitioners, forget the ground of basic goodness, the sacredness of all phenomena, and act in a degraded way. Enraged by this, the mamos express their legendary wrath. This wrath arises not from personal insult or violation, but from our own improper relationship to life.

The entire chanting session, perhaps a half hour or hour long, is a contemplation of cause and effect, of wrathful compassion and awareness. It’s also a contemplation of a kind of sacred outlook that restores balance in the world. By leaning into the message of the mamos, we pacify them and also their effect on us. The entire chant ends with the Vajrasattva mantra of primordial purity.